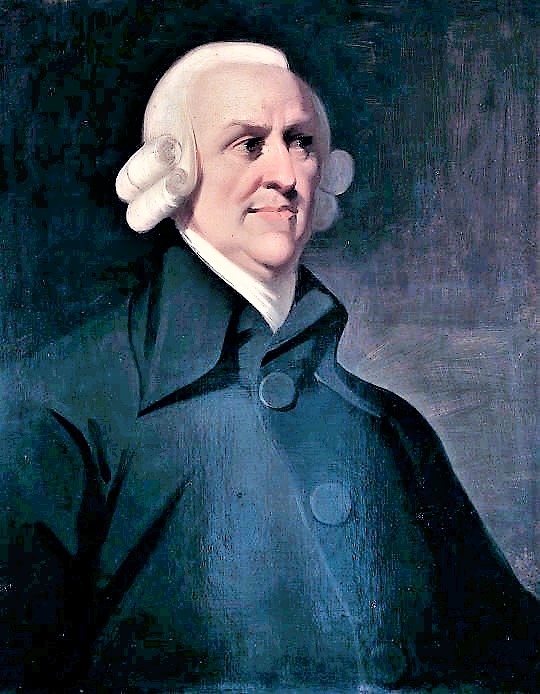

Adam Smith, Misanthrope

Adam Smith would, as is widely recognised, have been sceptical about the current vogue for ‘industrial strategy’: ‘The statesman who should attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no council or senate whatever, and which would nowhere be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had folly and presumption enough to fancy himself fit to exercise it.’ – Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter II And even more sceptical of current demands for protectionism: “[Trade restrictions,] by aiming at the impoverishment of all our neighbours, tend to render that very commerce insignificant and contemptible.” – WoN, IV, III But what is less widely recognised is that the misanthropic Smith was sceptical about everything. Smith was a socially awkward misanthrope who never married. The feminist writer Katrine Marcal recently wrote a critique of modern economics under the title “Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?” A fair question; for most of Smith’s life the answer was his mother, who predeceased him by only six years. Businessmen who profess admiration for Smith should be warned that such admiration was not reciprocated: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” – WoN, I, X And traders found even less favour: “…an order of men, whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.” – WoN, I, XI Smith was also critical of bankers, with cautionary advice even more relevant today: “Though the principles of the banking trade may appear somewhat abstruse, the practice is capable of being reduced to strict rules. To depart upon any occasion from these rules, in consequence of some flattering speculation of extraordinary gain, is almost always extremely dangerous, and frequently fatal to the banking company which attempts it.” – WoN, V, I Politicians, of course, were firmly in the firing line: “The violence and injustice of the rulers of mankind is an ancient evil, for which, I am afraid, the nature of human affairs can scarce admit of a remedy.” – WoN, IV, III And the great imperial project in which Britain was then engaged was not applauded: “To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers, may at first sight, appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers, but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers.” – WoN, IV, VII The rich received little respect: “With the greater part of rich people, the chief enjoyment of riches consists in the parade of riches, which in their eye is never so complete as when they appear to possess those decisive marks of opulence which nobody can possess but themselves.” – WoN, I, XI An observation as relevant to states as to individuals: “In public, as well as in private expences, great wealth may, perhaps, frequently be admitted as an apology for great folly.” – WoN, IV, V Smith had little time for quantitative economics: “I have no great faith in political arithmetic, and I mean not to warrant the exactness of either of these computations.” – WoN, IV, V Nor for the universities of his time: “The discipline of colleges and universities is in general contrived, not for the benefit of the students, but for the interest, or more properly speaking, for the ease of the masters.” – WoN, V, I And the University of Oxford was selected for particular scorn: “In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” – WoN, V, I

Adam Smith, Misanthrope Read More »